The Fascinating Physiology Of The Colon

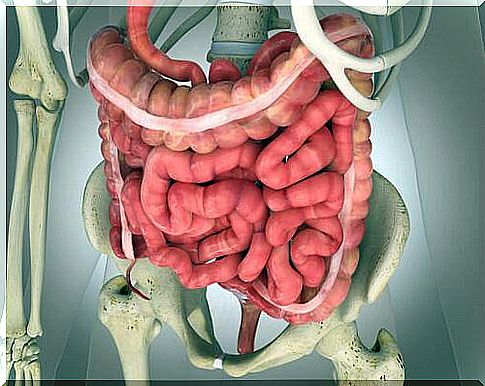

The physiology of the colon is really fascinating. The feces travel through the colon due to a mixture of movement and forward thrust. At the same time, various substances are absorbed and secretions are given off.

In today’s article we want to tell you about the fascinating physiology of the colon. That means that today it’s all about the very end of your digestive tract.

peristalsis

This term describes the contractions of your digestive tract. Your goal is to get the feces into the anus. In other words, these movements are pushing forward movements.

Colon physiology: bowel movements

Analogous to the processes in the small intestine, stool can also be divided into mixed movements and drive movements.

- Mixed movements are a combination of contractions of the circular and longitudinal muscles of the colon (colon). These movements push the unstimulated part of the colon outward in a sac-like shape. These bulges are called “haustra”.

Minutes later, this process repeats itself, pushing the feces further through your colon. Like your intestines are being “milked”. In this way, the entire fecal matter always remains on the outside of the intestinal wall. This facilitates the absorption of hydro-electrolytes.

- The drive movements depend on the “mass movements”. These movements are a modified form of peristalsis. They unite the movement of the colon. This pushes the feces further through the intestines. Mass movements occur three times a day and last 30 minutes each time.

How do these movements start in your gut?

The mass movements are a reaction to the expansion of the stomach and duodenum (gastrocolic and duodenal reflex). These reflexes can also be triggered in response to irritation. For example, irritation occurs when you have ulcerative colitis.

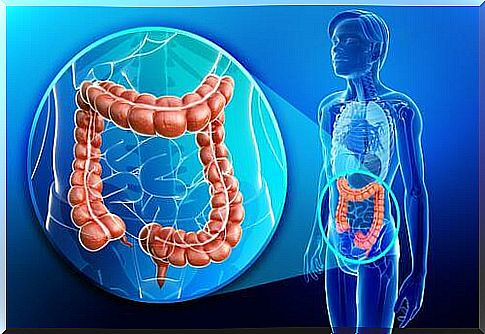

The role of the ileocecal valve

The ileocecal valve prevents the chyme (pre-digested chyme from the stomach) from flowing back into the ileum as soon as it has reached your colon.

The contractions of the ileum sphincter control the movements of the chyme pulp. In addition, the reflexes of your appendix regulate and control the peristalsis in the ileum. In doing so, they help prevent backflow.

When the walls of the appendix expand, they send out signals that increase the contraction of the sphincter. At the same time, intestinal peristalsis is prevented.

What happens if these processes are disturbed ?

Generally one can say:

- Excessive bowel movements mean that fewer minerals and water can be absorbed. This in turn means that your stool becomes very soft or you even get diarrhea.

- Disruption of bowel movements causes excessive absorption of water and minerals. This makes your bowel movements very hard and can lead to constipation.

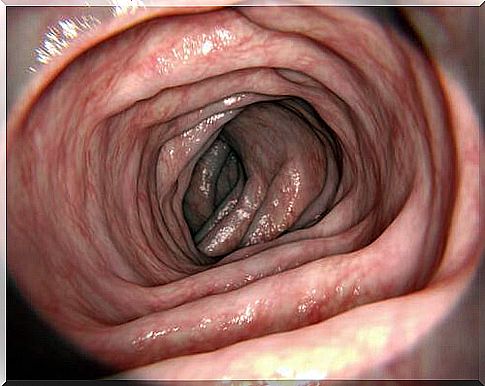

Colon physiology: defecation reflex (stool reflex)

The stool reflex (or defecation reflex) triggers the excretion of feces:

- I ntrin sic r eflex: It is triggered by the enteric nervous system (ENS), which is also called the “brain of the intestine”.

- Parasympathetic reflex : This is driven by the nerve fibers of the pelvis and serves to reinforce the intrinsic reflex.

How exactly does that happen?

When your feces reach the rectum, a signal is triggered, causing the intestinal walls to expand. This in turn triggers further signals that are conducted through the Auerbach plexus (part of the enteric nervous system).

In response to these signals, peristaltic wave movements occur, which spread from the colon (colon) down to the rectum. This will eventually push the feces out of the anus.

The myenteric plexus (Auerbach plexus) now sends out signals that relax the internal sphincter muscle . Then when the peristaltic waves reach your anus, the feces keep moving forward. The external sphincter is consciously relaxed.

In other words, afferent signals are sent to the spinal cord when the nerve fibers in your anus are stimulated. These signals pass through the parasympathetic nerve cords of the pelvic nerves and increase the peristalsis. This relaxes the internal sphincter muscle.

Colon Physiology: Substance Secretion

Which substances are secreted?

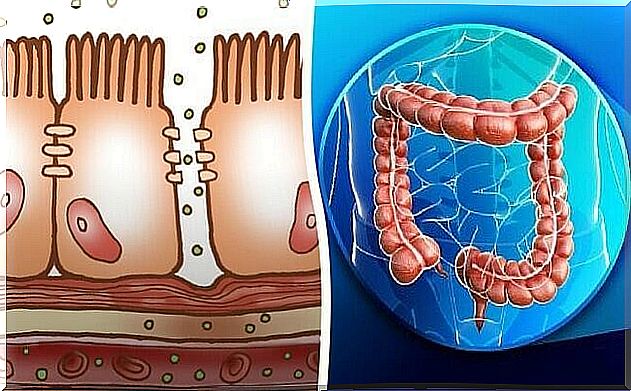

Only one type of mucus is formed in your colon. This secretion contains controlled amounts of bicarbonate ions (pH value> 8). This mucus is formed by mucous cells in the intestinal walls and the Lieberkühn glands (tubular glands in the small intestine). The bicarbonate is secreted by various epithelial cells. This secretion ensures that the mucus has an alkaline pH value.

How is the mucus formed?

The mucus formation takes place through the direct stimulation of the mucous cells. Besides, this also increases the response to stimulation of the pelvic nerves (parasympathetic innervation).

What is the function of the secretion of mucus?

The secretion of mucus has three functions:

- Firstly, the mucus protects your intestinal walls from possible scarring and also from acids from the feces (the pH value of the mucus is> 8 because of the bicarbonate ions it contains).

- Second, it holds the fecal matter together.

- And third, the mucus protects your intestines from harmful bacteria.

Colon physiology: absorption of various substances

Around 1500 milliliters of chyme (chyme) enter the large intestine every day. The majority of the water and electrolytes contained therein are absorbed in the proximal colon. As a result, your feces only contain around 100 milliliters of water and between 1 and 5 mEq of sodium and chlorine ions.

How exactly are substances absorbed in your colon?

The large intestine absorbs sodium by actively exchanging sodium for hydrogen ions. Thanks to the electrical gradient, some chlorine ions move passively into the interior of the cells. The remaining chlorine ions are absorbed in exchange with bicarbonate ions.

Your intestines absorb potassium through active transport as well as other ions such as calcium and magnesium.

The connections between cells in the colon are much closer than those in other parts of the digestive tract. For this reason, the sodium ions can be prevented from migrating back again. In this way, better absorption of sodium is achieved.

The natural steroid hormone aldosterone plays a key role in sodium absorption. The resulting concentration gradient allows the absorption of water by osmosis.

Featured Image courtesy of © wikiHow.com